Gian Lorenzo Bernini

| Gian Lorenzo Bernini | |

|---|---|

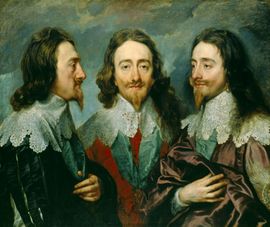

Portrait of Bernini is said to have used his own features in his David |

|

| Birth name | Gian Lorenzo Bernini |

| Born | December 7, 1598 Naples, Kingdom of Naples, in present-day Italy |

| Died | November 28, 1680 (aged 81) Rome, Papal States, in present-day Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Field | Sculpture, painting, architecture |

| Movement | Baroque |

| Works | David, Apollo and Daphne, The Rape of Proserpina, Ecstasy of Saint Theresa |

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (also spelled Gianlorenzo or Giovanni Lorenzo) (Naples, 7 December 1598 – Rome, 28 November 1680) was an Italian artist who worked principally in Rome. He was the leading sculptor of his age and also a prominent architect. In addition he painted, wrote plays, and designed metalwork and stage sets.

A student of Classical sculpture, Bernini possessed the unique ability to capture, in marble, the essence of a narrative moment with a dramatic naturalistic realism which was almost shocking. This ensured that he effectively became the successor of Michelangelo, far outshining other sculptors of his generation, including his rival, Alessandro Algardi. His talent extended beyond the confines of his sculpture to consideration of the setting in which it would be situated; his ability to be able to synthesise sculpture, painting and architecture into a coherent conceptual and visual whole has been termed by the art historian, Irving Lavin, the ‘unity of the visual arts’.[1] A deeply religious man, working in Counter Reformation Rome, Bernini used light as an important metaphorical device in the perception of his religious settings; often it was hidden light sources that could intensify the focus of religious worship,[2] or enhance the dramatic moment of a sculptural narrative.

Bernini was also a leading figure in the emergence of Roman Baroque architecture along with his contemporaries, the architect, Francesco Borromini and the painter and architect, Pietro da Cortona. Early in their careers they had all worked at the same time at the Palazzo Barberini, initially under Carlo Maderno and on his death, under Bernini. Later on, however, they were in competition for commissions and fierce rivalries developed, particularly between Bernini and Borromini.[3] Despite the arguably greater architectural inventiveness of Borromini and Cortona, Bernini’s artistic pre-eminence, particularly during the reigns of popes Urban VIII (1623–44) and Alexander VII (1655–1665), meant he was able to secure the most important commission in Rome of the day, St. Peter's Basilica. His design of the Piazza San Pietro in front of the Basilica is one of his most innovative and successful architectural designs.

During his long career, Bernini received many important commissions, many associated with the papacy. At an early age, he came to the attention of the papal nephew, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, and in 1621, at the age of only twenty three, he was knighted by Pope Gregory XV. Following his accession to the papacy, Urban VIII is reported to have said, "Your luck is great to see Cardinal Maffeo Barberini Pope, Cavaliere; but ours is much greater to have Cavalier Bernini alive in our pontificate".[4] Although he did not fare so well during the reign of Innocent X, under Alexander VII, he once again regained pre-eminent artistic domination and continued to be held in high regard by Clement IX.

Bernini and other artists fell from favour in later neoclassical criticism of the Baroque. It is only from the late nineteenth century that art historical scholarship, in seeking an understanding of artistic output in the cultural context in which it was produced, has come to recognise Bernini’s achievements and restore his artistic reputation.

Contents |

Early life

Bernini was born in Naples to a Mannerist sculptor, Pietro Bernini, originally from Florence, and Angelica Galante, a Neapolitan.[5][6] At the age of seven he accompanied his father to Rome, where his father was involved in several high profile projects.[7] There, as a boy, his skill was soon noticed by the painter Annibale Carracci and by Pope Paul V, and Bernini gained the patronage exclusively under Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the pope's nephew. His first works were inspired by antique Hellenistic sculpture.

Rise to master sculptor

Under the patronage of the Cardinal Borghese, young Bernini rapidly rose to prominence as a sculptor. Among the early works for the cardinal were decorative pieces for the garden such as "The Goat Amalthea with the Infant Zeus and a Faun", and several allegorical busts such as the "Damned Soul" and "Blessed Soul". By the age of twenty-two years, he completed the bust of Pope Paul V. Scipione's collection in situ at the Borghese gallery chronicles his secular sculptures, with a series of masterpieces:

- "Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius" (1619) depicts three ages of man from various viewpoints, borrowing from a figure in a Raphael fresco. In The Aeneid, Aeneas flees the burning city of Troy, carrying his father and his son at his heels. His father holds the household gods and his son holds the eternal flame. Aeneas is the founder of Latium, later Italy, and the father of the Romans. The sculpture is in a very Mannerist upwards spiral.

- "The Rape of Proserpina", (1621–22) recalls Giambologna's Mannerist "Rape of the Sabine Women", and displays a masterful attention to detail, including the abductor "dimpling" the woman's marble skin.

- "Apollo and Daphne" (1622–25) has been widely admired since Bernini's time; along with the subsequent sculpture of David it represents the introduction of a new sculptural aesthetic. It depicts the most dramatic and dynamic moment in one of Ovid's stories in his Metamorphoses. In the story, Apollo, the god of light, scolded Eros, the god of love, for playing with adult weapons. In retribution, Eros wounded Apollo with a golden arrow that induced him to fall madly in love at the sight of Daphne, a water nymph sworn to perpetual virginity, who, in addition, had been struck by Eros with a lead arrow which immunized her from Apollo's advances. The sculpture depicts the moment when Apollo finally captures Daphne, yet she has implored her father, the river god, to destroy her beauty and repel Apollo's advances by transforming her into a laurel tree. This statue succeeds at various levels: it depicts the event and also represents an elaborate conceit of sculpture. This sculpture tracks the metamorphoses as a representation in stone of a person changing into lifeless vegetation; in other words, while a sculptor's art is to change inanimate stone into animated narrative, this sculpture narrates the opposite, the moment a woman becomes a tree.

- "David" (1623–24) like the "Apollo and Daphne", was a revolutionary sculpture for its time. Both depict movement in a way not previously attempted in stone. The biblical youth is taut and poised to rocket his projectile. Famous "David"s sculpted by Bernini's Florentine predecessors had portrayed the static moment before and after the event; Michelangelo portrayed David prior to his battle with Goliath, to intimate the psychological fortitude necessary for attempting such a gargantuan task; the contemplative intensity of Michelangelo's "David" or the haughty effeteness of Donatello's and Verrocchio's "David"s are all, nonetheless, portraying moments of stasis. The twisted torso, furrowed forehead, and granite grimace of Bernini's "David" epitomize Baroque fixation with dynamic movement and emotion over High Renaissance stasis and classical severity. Michelangelo expressed David's psychological fortitude, preparing for battle; Bernini captures the moment when he becomes a hero.

Mature sculptural output

Bernini's sculptural output was immense and varied. Among his other well-known sculptures: the "Ecstasy of St. Theresa", in the Cornaro Chapel (see Bernini's Cornaro chapel: the complete work of art found in the Baroque section), Santa Maria della Vittoria, and the now-hidden "Constantine", at the base of the Scala Regia (which he designed). He was given the commission for the tomb of the Barberini Pope in St Peters. He helped design the Ponte Sant'Angelo, sculpting two of the angels, soon replaced by copies by his own hand, while the others were made by his pupils based on his designs.

At the end of April 1665, at the height of his fame and powers, he travelled to Paris, where he remained until November; he met Paul Fréart de Chantelou who kept a Journal of Bernini's visit.[8] Bernini's international popularity was such that on his walks in Paris the streets were lined with admiring crowds. This trip, encouraged by Father Oliva, general of the Jesuits, was a response to the repeated requests for his works by King Louis XIV. Here Bernini presented some designs for the east front of the Louvre. which were ultimately rejected. He soon lost favor at the French court as he praised the art and architecture of Italy over that of France; he said that a painting by Guido Reni was worth more than all of Paris. The sole work remaining from his time in Paris is a bust of Louis XIV, which set the standard for royal portraiture for a century.

Architecture

Bernini's architectural works include sacred and secular buildings and sometimes their urban settings and interiors.[9] He made adjustments to existing buildings and designed new constructions. Amongst his most well known works is the Piazza San Pietro (1656–67), the piazza and colonnades in front of St Peter's and the interior decoration of the Basilica. Amongst his secular works are a number of Roman palaces: following the death of Carlo Maderno, he took over the supervision of the building works at the Palazzo Barberini from 1630 on which he worked with Borromini; the Palazzo Ludovisi (now Palazzo Montecitorio)(started 1650); and the Palazzo Chigi (now Palazzo Chigi-Odescalchi) (started 1664).

His first architectural projects were the façade and refurbishment of the church of Santa Bibiana (1624-6) and the St. Peter's baldachin (1624–1633), the bronze columned canopy over the high altar of St. Peter's Basilica. In 1629, and before the Baldacchino was complete, Urban VIII put him in charge of all the ongoing architectural works at St Peter's. However, due to political reasons and miscalculations in his design of the bell-towers for St. Peter's, Bernini fell out of favor during the Pamphili papacy of Innocent X.[10] Never wholly without patronage, Bernini then regained a major role in the decoration of St. Peter's with the Pope Alexander VII Chigi, leading to his design of the piazza and colonnade in front of St. Peter's. Further significant works by Bernini at the Vatican include the Scala Regia, (1663-6) the monumental grand stairway entrance to the Vatican Palace and the Cathedra Petri, the Chair of Saint Peter, in the apse of St. Peter's.

Bernini did not build many churches from scratch, rather his efforts were concentrated on pre-existing structures, and in particular St. Peter's. He fulfilled three commissions for new churches; his stature allowed him the freedom to design the structure and decorate the interiors in a consistent manner. Best known is the small oval baroque church of Sant'Andrea al Quirinale, a work which Bernini's son, Domenico, reports his father was very pleased with.[11] Bernini also designed churches in Castelgandolfo (San Tommaso da Villanova, 1658–61) and Ariccia (Santa Maria Assunta, 1662-4).

When Bernini was invited to Paris in 1665 to prepare works for Louis XIV, he presented designs for the east facade of the Louvre Palace but his projects were ultimately turned down in favour of the more stern and classic proposals of the French doctor and amateur architect Claude Perrault [12], signalling the waning influence of Italian artistic hegemony in France. Bernini's projects were essentially rooted in the Italian Baroque urbanist tradition of relating public buildings to their settings, often leading to innovative architectural expression in urban spaces like piazze or squares. However, by this time, the French absolutist monarchy now preferred the classicising monumental severity of Perrault's facade, no doubt with the added political bonus that it been designed by a Frenchman. The final version did, however, include Bernini's feature of a flat roof behind a Palladian balustrade.

In 1639, Bernini bought property on the corner of the via Mercede and the via del Collegio di Propoganda Fide in Rome. On this site he built himself a palace, the Palazzo Bernini, at what are now Nos 11 and 12 via della Mercede. He lived at No. 11 but this was extensively changed in the nineteenth century. It has been noted how very galling it must have been for Bernini to witness through the windows of his dwelling, the construction of the tower and dome of Sant'Andrea delle Fratte by his rival, Borromini, and also the demolition of the chapel that he, Bernini, had designed at the Collegio di Propoganda Fide to see it replaced by Borromini's chapel.[13]

Fountains in Rome

True to the decorative dynamism of Baroque, among Bernini's most gifted creations were his Roman fountains that were both public works and papal monuments. His fountains include the Fountain of the Triton or Fontana del Tritone and the Barberini Fountain of the Bees, the Fontana delle Api.[14] The Fountain of the Four Rivers or Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi in the Piazza Navona is a masterpiece of spectacle and political allegory. An oft-repeated, but false, anecdote tells that one of the Bernini's river gods defers his gaze in disapproval of the facade of Sant'Agnese in Agone (designed by the talented, but less politically successful, rival Francesco Borromini). However, the fountain was built several years before the façade of the church was completed.

Bernini was also the author of the statue of the Moor in La Fontana del Moro in Piazza Navona (1653).

Marble portraiture

Bernini also revolutionized marble busts, lending glamorous dynamism and animation to the stony stillness of portraiture. Starting with the immediate pose, leaning out of the frame, of bust of Monsignor Pedro de Foix Montoya at Santa Maria di Monserrato, Rome. The once-gregarious Cardinal Scipione Borghese, in his bust is frozen in conversation.

His most famous portrait is that of Costanza Bonarelli (c. 1637). It does not portray divinity or royalty, but a woman in a moment of disheveled privacy. Bernini had an affair with Costanza, who was the wife of one of Bernini's assistants. When Bernini suspected Costanza to be involved with his brother, he badly beat him and ordered a servant to slash her face with a razor. Pope Urban VIII intervened on his behalf and he was fined.[15]

Bernini also gained royal commissions from outside Italy, for subjects such as Louis XIV, Cardinal Richelieu, Francesco I d'Este, Charles I of England and Henrietta Maria. The last two were produced in Italy from portraits made by Van Dyck (now in the royal collection), though Bernini preferred to produce portraits from life - the bust of Charles was lost in the Whitehall Palace fire of 1698 and that of Henrietta Maria was not undertaken due to the outbreak of the English Civil War.[16][17]

An exhibition co-organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, and the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, explored Bernini's portraits: Bernini and the Birth of Baroque Portrait Sculpture, August 5–October 26, 2008.

Other works

The Elephant and Obelisk, affectionately as Bernini's Chick by the Roman people, is located in the Piazza della Minerva and in front of the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva. Pope Alexander VII decided that he wanted an ancient Egyptian obelisk to be erected in the piazza and in 1665 he commissioned Bernini to create a sculpture to support the obelisk. The sculpture of an elephant bearing the obelisk on its back was created by one of Bernini's students, Ercole Ferrata and finished in 1667. An inscription on the base aligns the Egyptian goddess Isis and the Roman goddess Minerva with the Virgin Mary who the church is dedicated to.[18] A popular antecdote concerns the elephant's smile. To find out why it is smiling, the viewer must head around to the rear end of the animal and to see that its muscles are tensed and its tail is shifted to the left as if it were defecating. The animal's rear is pointed directly at the office of Father Domenico Paglia, a Dominican friar, who was one of the main antagonists of Bernini and his artist friends, as a final salute and last word.

Bernini worked along with Ercole Ferrata to create a much admired fountain for the Lisbon palace of the Portuguese nobleman, the Count of Ericeira. For the same patron he also created a series of paintings with the battles of Louis XIV as subject. These works were lost as the palace, its great library and the rich art collection of the Counts of Ericeira, were destroyed along with most of central Lisbon as a result of the great earthquake of 1755.

The death of his patron Urban VIII in 1644 and the election of the Pamphilj pope, Innocent X, initially marked a downturn in Bernini's career and released a series of opportunities for Bernini's rivals. However, within several years, Innocent reinstated him at St Peter's to work on the extended nave and commissioned the Four Rivers fountain in the Piazza Navona. At the time of Innocent's death in 1655, Bernini was the arbiter of public artistic taste in Rome. His artistic ascendency continued under Alexander VII.

He died in Rome in 1680, and was buried in the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore.

Among the many who worked under his supervision were Luigi Bernini, Stefano Speranza, Giuliano Finelli, Andrea Bolgi, Filippo Parodi, Giacomo Antonio Fancelli, Lazzaro Morelli, Francesco Baratta, and Francois Duquesnoy. Among his rivals in architecture were Francesco Borromini and Pietro da Cortona; in sculpture, Alessandro Algardi.

Two years after his death, Queen Christina of Sweden, then living in Rome, commissioned Filippo Baldinucci to write his biography.[19]

Selected works

Sculpture

- Bust of Giovanni Battista Santoni (c. 1612) - Marble, life-size, Santa Prassede, Rome

- "Martyrdom of St. Lawrence" (1614–1615) - Marble, 66 x 108 cm, Contini Bonacossi Collection, Florence

- "The Goat Amalthea with the Infant Jupiter and a Faun" (1615) - Marble, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- "St. Sebastian" (c. 1617) - Marble, Thyssen Bornemisza Museum, Madrid

- "A Faun Teased by Children" (1616–1617) - Marble, height 132,1 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- "Aeneas, Anchises, and Ascanius" (1618–1619) - Marble, height 220 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- "Damned Soul" (1619) - Palazzo di Spagna, Rome

- "Blessed Soul" (1619) - Palazzo di Spagna, Rome

- "Apollo and Daphne" (1622–1625) - Marble, height 243 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- St. Peter's Baldachin (1624) - Bronze, partly gilt, Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican City

- "Charity with Four Children" (1627–1628) - Terracotta, height 39 cm, Museo Sacro, Musei Vaticani, Vatican

- "David" (1623–1624) - Marble, height 170 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Fontana della Barcaccia (1627–1628) - Marble, Piazza di Spagna, Rome

- Bust of Monsignor Pedro de Foix Montoya (c. 1621) - Marble, life-size, Santa Maria di Monserrato, Rome

- "Neptune and Triton" (1620) - Marble, height 182,2 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- "The Rape of Proserpina" (1621–1622) - Marble, height 295 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Fontana del Tritone (1624–1643) - Travertine, over life-size, Piazza Barberini, Rome

- Tomb of Pope Urban VIII (1627–1647) - Golden bronze and marble, figures larger than life-size, Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican City

- Bust of Thomas Baker (1638) - Marble, height 81,6 cm, Victoria and Albert Museum, London

- Bust of Costanza Bonarelli (c. 1635) - Marble, height 70 cm, Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

- "Charity with Two Children" (1634) - Terracotta, height 41.6 cm, Museo Sacro, Musei Vaticani, Vatican City

- "Saint Longinus" (1631–1638) - Marble, height 450 cm, Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican City

- Bust of Scipione Borghese (1632) - Marble, height 78 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Bust of Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1632) - Marble, Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican City

- Bust of Pope Urban VIII (1632–1633) - Bronze, height 100 cm, Museo Sacro, Musei Vaticani, Vatican City

- Bust of Cardinal Armand de Richelieu (1640–1641) - Marble, Musée du Louvre, Paris

- Memorial to Maria Raggi (1643) - Gilt bronze and coloured marble, Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome

- "Truth" (1645–1652) - Marble, height 280 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Bust of Pope Leo X (1647), Palazzo Doria Pamphilij, Rome

- "Ecstasy of St. Theresa" (1647–1652) - Marble, Cappella Cornaro, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

- Loggia of the Founders (1647–1652) Marble, Cappella Cornaro, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

- Bust of Urban VIII - Marble, Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican City

- Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi (1648–1651) - Travertine and marble, Piazza Navona, Rome

- Corpus (sculpture) (1650) - Bronze, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Canada.

- "Daniel and the Lion" (1650) - Marble, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

- Francesco I d'Este (1650–1651) - Marble, height 107 cm, Galleria Estense, Modena

- Fountain of the Moor (1653–1654) - Marble, Piazza Navona, Rome

- "Constantine" (1654–1670) - Marble, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican City

- "Daniel and the Lion" (1655) - Terracotta, height 41.6 cm, Museo Sacro, Musei Vaticani, Vatican City

- "Habakkuk and the Angel" (1655) - Terracotta, height 52 cm, Museo Sacro, Musei Vaticani, Vatican City

- Altar Cross (1657–1661) - Gilt bronze corpus on bronze cross, height: corpus 43 cm, cross 185 cm, Treasury of San Pietro, Vatican City

- Throne of Saint Peter (1657–1666) - Marble, bronze, white and golden stucco, Basilica di San Pietro, Rome

- Statue of Saint Augustine (1657–1666) - Bronze, Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican City

- "Constantine" (1663–1670) - Marble with painted stucco drapery, Scala Regia, Vatican Palace, Rome

- "Standing Angel with Scroll" (1667–1668) - Clay, terracotta, height: 29,2 cm, Fogg Art Museum, Cambridge

- "Angel with the Crown of Thorns" (1667–1669) - Marble, over life-size, Sant'Andrea delle Fratte, Rome

- "Angel with the Superscription" (1667–1669) - Marble, over life-size, Sant'Andrea delle Fratte, Rome

- "Elephant of Minerva" (1667–1669) - Marble, Piazza di Santa Maria sopra Minerva, Rome

- Bust of Gabriele Fonseca (1668–1675) - Marble, over life-size, San Lorenzo in Lucina, Rome

- Equestrian Statue of King Louis XIV (1669–1670) - Terracotta, height 76 cm, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Bust of Louis XIV (1665) - Marble, height 80 cm, Musée National de Versailles, Versailles

- "Herm of St. Stephen, King of Hungary" - Bronze, Cathedral Treasury, Zagreb

- "Saint Jerome" (1661–1663) - Marble, height 180 cm, Cappella Chigi, Duomo, Siena

- Tomb of Pope Alexander VII (1671–1678) - Marble and gilded bronze, over life-size, Basilica di San Pietro, Vatican City

- "Blessed Ludovica Albertoni" (1671–1674) - Marble, Cappella Altieri-Albertoni, San Francesco a Ripa, Rome

Paintings

Bernini's activity as a painter was a sideline which he did mainly in his youth. Despite this his work reveals a sure and brilliant hand, free from any trace of pedantry. He studied in Rome under his father, Pietro, and soon proved a precocious infant prodigy. His work was immediately sought after by major collectors.

- Saint Andrew and Saint Thomas (c. 1627) - Oil on canvas, 59 x 76 cm, National Gallery, London

- Portrait of a Boy (c. 1638) - Oil on canvas, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Self-Portrait as a Young Man (c. 1623) - Oil on canvas, Galleria Borghese, Rome

- Self-Portrait as a Mature Man (1630–1635) - Oil on canvas, Galleria Borghese, Rome

References

- ↑ Lavin, Irving. Bernini and the Unity of the Visual Arts, Oxford University Press, 1980

- ↑ such as his 1628 design for the Forty Hours Devotion, Hibbard, Howard, Bernini, 1965,p.136

- ↑ See Mileti, Nick J. Beyond Michelangelo, the deadly rivalry between Bernini and Borromini, Xlibris Corporation, Philadelphia, Pa., 2005; Morrissey, Jake. Genius in the design: Bernini, Borromini and the rivalry that transformed Rome, Harper Perennial, New York and London, 2005

- ↑ Hibbard, Howard, Bernini, 1965: 68

- ↑ Gallery.ca

- ↑ Gale, Thomson. Gian Lorenzo Bernini Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2004.

- ↑ Gianlorenzo Bernini

- ↑ See Gould, Cecil. Bernini in France, an episode in Seventeenth Century History, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1981

- ↑ See Marder, Tod A. Bernini and the Art of Architecture Abbeville Press, New York and London, 1998

- ↑ See McPhee, Sarah. Bernini and the bell towers: architecture and politics at the Vatican, Yale University Press, 2002

- ↑ Magnuson Torgil, Rome in the Age of Bernini, Volume II, Almqvist & Wiksell, Stockholm, 1986: 202

- ↑ Probably made in collaboration with the collaboration of Lebrun and {Le Vau]], Blunt, Anthony. Architecture in France 1500-1700, Pelican History of Art, 1953, p. 232

- ↑ Blunt, Anthony. Guide to Baroque Rome, Granada, 1982, p. 166

- ↑ This was dismantled in the nineteenth century and reassembled (incorrectly) in the twentieth in the Via Veneto. A second Fontana delle Api in the Vatican has sometimes been attributed to Bernini of which Blunt has written, "Borromini is documented as having carved the fountain in 1626, but it is not certain whether he made the design for it, and it has also been attributed -not very plausibly- to Bernini". Blunt, Anthony. Borromini, Belknap Harvard, 1979, 17

- ↑ "Biographies - Gian Lorenzo Bernini", National Gallery of Canada, http://www.gallery.ca/bernini/en/bernini.htm, retrieved 29 October 2009

- ↑ Triple Portrait of Charles I

- ↑ Lionel Cust, Van Dyck (Read books, 2007) - ISBN 1406774529

- ↑ Heckscher, W. Bernini's Elephant and Obelisk, Art Bulletin, XXIX, 1947, p. 155.

- ↑ Baldinucci, Filippo. Life of Bernini. Translated from the Italian by Enggass, C. University Park, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006

19. Daniela Del Pesco, Bernini in Francia. Paul de Chantelou e il 'Journal de voyage du Cavalier Bernin en France' (Napoli: Electa Napoli 2007), 575 pp.

External links

- Checklist of Bernini's architecture and sculpture in Rome

- Excerpts from The life of the Cavaliers Bernini

- Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the "A World History of Art"

- Extract on Bernini from Simon Schama's The Power of Art

- Photographs of Bernini's Santa Maria Assunta

- smARThistory: Ecstacy of Saint Teresa, Cornaro Chapel, Santa Maria della Vittoria, Rome

- Virtual tour of Rome visiting Bernini's key works